13 questions to ask about casinos and Japan

May 14, 2014 Newsdesk Features, Japan, Latest News, Top of the deck

“If I live long enough to see it legalised, I’ll look to sell casino equipment into the Japanese market.” That was the view of one senior executive (in seemingly robust health) from the supplier side of the industry canvassed by GGRAsia recently.

Proponents of the initial bill to legalise casino resorts in Japan said as recently as April that it might be possible to pass it prior to the country’s parliament the Diet adjourning in June.

Brokerage CLSA estimated in a report in February that the Japanese casino market could be worth US$40 billion (HK$310 billion) by 2025, if a second phase of nine projects opens to complement the three it thinks likely to launch in Tokyo, Osaka and Okinawa respectively by 2020.

Why is there such as disconnection between the bullish views of domestic lobbyists, Western casino operators and many analysts on one side, and the extremely bearish ones of some casino industry veterans and casino industry suppliers on the other?

It would be too easy simply to ascribe it to bad faith on the part of casino operators that would like to support the current pricing of their stocks, and bankers who would look to earn healthy fees for arranging debt to service such casino industry expansion – possibly with some fresh local share listings later.

Nonetheless, investors do deserve information that goes beyond glib wish fulfilment. For that reason on the eve of the Japan Gaming Congress in Tokyo starting today, GGRAsia has compiled a list of questions we think institutional investors in casino names should consider asking their advisors about Japan.

Q. Have the sell side analysts and casino operators lobbying for casinos in japan canvassed a wide range of political and social views inside the country about the prospects for casino gaming?

The Japanese people who tend to talk to foreign investors and journalists about the issue are pro-casino. In April it was however also reported that the National Police Agency – which has purportedly invested in pachinko industry technology via its pension fund and which is also responsible for supervising the pachinko industry – had dropped its long-standing opposition to casinos.

But Japan is a mature democracy. It may be harder to fast track policies on potentially polarising issues such as casino gaming than it is in Macau or even Singapore. That’s certainly been the experience in Taiwan.

Q. Will Japan allow foreign firms to have majority ownership of a casino project?

Unlike Macau at the start of its casino liberalisation process, Japan has plenty of domestic large cap corporations sitting on cash and hungry for improved returns. The same goes for the domestic banking sector.

As a paper from Hyun Song Shin of Princeton University in November last year pointed out, Japan knows from the 1980s the danger of expanding broad domestic money supply via the route of corporate time deposits. That’s one of the reasons current prime minister Shinzo Abe wants to spend, spend, spend Japan’s way out of stagnation.

Major Japanese corporations own more than 225 trillion yen (US$2.2 trillion) of low-yielding Japanese government bonds according to the Bank of Japan. The fact such corporations currently have more cash than debt is an indicator of the dearth of domestic investment opportunities.

Q. Foreign firms have the expertise in casino resort management, but is that enough bargaining power for them to demand from the Japanese authorities majority equity ownership of casino projects?

The involvement of the nationalistically minded Japan Restoration Party in the drafting of an initial bill to legalise casinos is being read by casino proponents as a sign of growing consensus on the issue. But consensus on the principle of building casino resorts, doesn’t necessarily mean there’s also consensus on majority foreign ownership.

Q. Is the current pachinko market a reliable guide to likely future demand for casino gaming? And even if it is, is that a good thing?

The impressive ‘sales’ figures usually quoted by the pachinko industry (19.1 trillion yen or US$187.5 billion in 2012 according to the Japan Productivity Center) are actually for ‘drop’ (the total money exchanged by players at the parlours to get the steel balls needed to play). That doesn’t equate to the actual ‘win’ accruing to the operators (the amount left after prizes are paid). ‘Win’ is probably one tenth of that headline number.

Pachinko is a mechanical game and officially designated by the Japanese authorities as a pastime involving skill. It’s almost impossible to define a meaningful house edge (ratio of the average loss to the initial bet) market wide for pachinko. It can’t be determined via the calibration of a random number generator that is then tested by technical compliance companies as would happen with a casino slot.

Nonetheless the pachinko parlour operators base their margin on things they can control. They can configure machines to make it easier or harder to win on them, and they also impose a differential between the price they sell the balls to players, and the price at which they buy back those balls that don’t win the top prizes. Opinions vary on what percentage of pachinko sales is converted to ‘win’ for the operators, but 10 percent is a figure quoted by some experts.

In slot gaming, house edge can be as low as two percent or as high as 15 percent. But using pachinko ‘drop’ to predict the success of casino slot gaming in Japan is a bit like trying to predict the size of a rugby crowd based on attendances at soccer matches. And that’s not even factoring in the culture-specific appeal of pachinko, which has been tried previously (and unsuccessfully) in Macau.

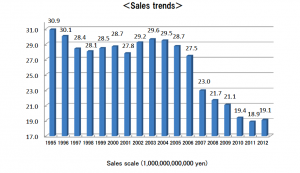

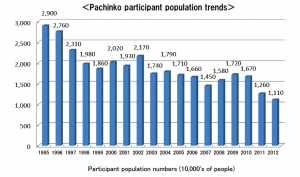

In any case, the Japan Productivity Center’s White Paper of Leisure 2013 says both sales and just as importantly participation rates for pachinko have been falling from a peak achieved in 1995.

In 2012 participation was estimated at 11.1 million people out of a population that year at 126 million. That was a 62 percent decline on the 29 million who participated in 1995. In 2012 pachinko sales rose slightly year-on-year to 19.1 trillion yen but they were still 38 percent down on the 30.9 trillion yen achieved in 1995.

Q. What’s the likely return on invested capital for Japanese casino resorts?

This question relates to all the previous ones. Sheldon Adelson of Las Vegas Sands Corp has previously mentioned he expects a 20 percent annual ROIC in markets where the company seeks to invest. That sort of return has also been mentioned privately by other operators in relation to Japan.

Q. Is the push for a Japanese casino industry really government fiscal stimulus by means other than central bank quantitative easing? If so, that may make the policy politically desirable domestically but does it also reduce the commercial logic for building them?

According to Dealogic, Japanese large corporate loans, defined as US$1 billion or more, fell 25 percent to US$144 billion last year from US$192 billion in 2012.

Praveen Choudhary, managing director of Morgan Stanley in Hong Kong said in a report about the prospects for Japan casino resorts – titled ‘Tempered Enthusiasm’ and dated April 23 – that: “In the last six months, many global gaming operators have tried to beat each other in terms of the amount of money (US$5-10 billion) they would spend if awarded the licence. This competition, along with rising construction costs and limited labour, would push the overall budget for a casino in Tokyo to around US$8-10 billion. With a higher tax regime (including revenue tax, entry fees and corporate income tax) and an overall market size of US$10 billion to be divided among several casinos, the returns could disappoint these casino operators.”

Q. What tax rate(s) will be imposed on casino gaming? Will there be a levy fee on Japanese entering the casinos? Will Macau-style junkets be allowed?

See above. We might not know the answer to any or all of those questions until the second piece of legislation aimed at regulating the casino industry.

Q. What is the likely time gap between the first piece of enabling legislation to legalise casinos and the second piece of legislation regulating them?

‘Expert’ estimates seen by GGRAsia have ranged from six months to six years, suggesting nobody really knows for sure.

Q. Will the choice of resort location(s) be decided by the time of the enactment of the first – enabling bill – or in the second, regulating, statute?

On March 11, GamblingCompliance.com reported that Hokkaido and Nagasaki were studying the possibility of integrated resorts, but added Tokyo was “still neutral” on the subject.

Q. What is the likely proportion of foreign players to domestic players?

The rationale advanced by the Singapore government for bringing casino resorts to Singapore was to boost foreign tourism. The Japanese government says it wants to boost foreign visitors to Japan from an expected 11 million this year to 20 million by 2020, when Tokyo hosts the Summer Olympics.

But Singapore introduced tougher regulations on responsible gambling and made it easier for local families to seek exclusion for relatives after it became clear that there was a large market in Singapore for local players.

Tokyo Disneyland is not a casino resort, but it is a big regional attraction. Only one million of the resort’s 31 million visitors in 2013 were from outside Japan according to the venue’s owner and operator, Oriental Land Co. That’s just 3.2 percent of the resort’s visitors overall.

Q. Who are the domestic high roller players?

Veteran casino executives with experience of working in Las Vegas, Macau and the Philippines tell GGRAsia that Japanese high rollers haven’t been seen in any great numbers since Japan’s export-driven boom of the late 1970s and 1980s.

Q. What impact if any is the fraught political relationship between Japan and China likely to have on the flow of Chinese players to Japanese casino resorts?

Who knows? But we do know that in 2012, during the long-running feud between the countries over islands in the East China Sea – called the Senkaku in Japan and the Diaoyu in China – Japan’s auto exports to China fell 80 percent year-on-year in the course of three months.

Q. What percentage of local staff employed by the IRs are likely to speak fluent Chinese and/or English?

The Ministry of Education’s four-page document, outlining the country’s education policy on foreign languages, states: “In principle English should be selected for foreign language activities.” It makes no mention of Chinese language teaching.

According to the Ministry, English is a required subject of the country’s college entrance exam. In 2013, 570,000 students took the exam out of a population of 127 million – 0.45 percent of the population. In South Korea, 650,000 students out of a population of 50 million took a college entrance exam with a compulsory English element, or 1.3 percent of the population. And Japan’s fertility rate per woman is 0.11 children higher than S. Korea’s.

Related articles

-

Universal Ent raises US$800mln to...

Universal Ent raises US$800mln to...Jul 24, 2024

-

CLSA trims forecast for Macau GGR,...

CLSA trims forecast for Macau GGR,...Jul 17, 2024

More news

-

Donaco EBITDA up y-o-y to above US$4mln...

Donaco EBITDA up y-o-y to above US$4mln...Jul 26, 2024

-

HK listed Palasino upgrades Czech...

HK listed Palasino upgrades Czech...Jul 26, 2024

Latest News

Jul 26, 2024

Border-casino operator Donaco International Ltd has achieved a 164.17-percent year-on-year increase in its latest quarterly group earnings before interest, taxation, depreciation and amortisation...Sign up to our FREE Newsletter

(Click here for more)

(Click here for more)

Pick of the Day

”We’ve got more traction outside of Macau at the moment. But Macau’s going be a bigger focus for us”

David Punter

Regional representative at Konami Australia

Most Popular

Sheraton brand to exit Londoner Macao, to be Londoner Grand July 25, 2024

Sheraton brand to exit Londoner Macao, to be Londoner Grand July 25, 2024  Macau regulator probes unlicensed gaming agents July 24, 2024

Macau regulator probes unlicensed gaming agents July 24, 2024  Philippines gives 20k aliens in POGOs 60 days to leave July 25, 2024

Philippines gives 20k aliens in POGOs 60 days to leave July 25, 2024  Philippines-listed DigiPlus says not affected by POGO ban July 24, 2024

Philippines-listed DigiPlus says not affected by POGO ban July 24, 2024  Sands China 2Q EBITDA down q-o-q amid low hold, renovation July 25, 2024

Sands China 2Q EBITDA down q-o-q amid low hold, renovation July 25, 2024